navigating on the command line#

Now that we’ve had chance to use the shell a bit, let’s see how we can use it to interact with, and navigate, the filesystem.

the filesystem#

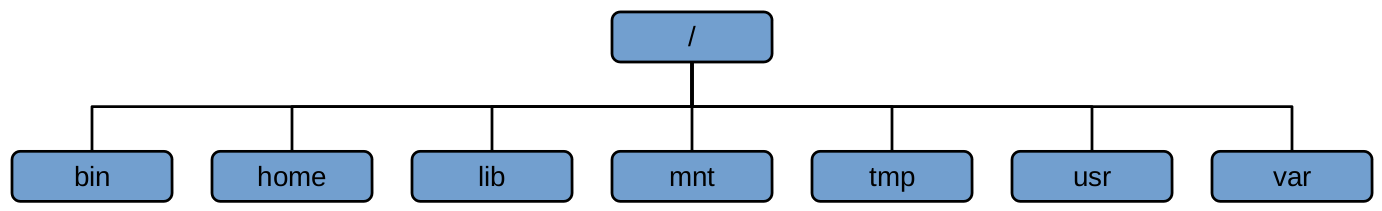

We should probably start, however, by discussing what “the filesystem” actually means. In effect, it’s how the operating

system stores and retrieves data. Most operating systems have a hierarchical directory structure - that is, the

filesystem is organized like an upside-down tree, starting from a single “root” folder. On Unix-like systems, the root

directory is /.

Most Unix-like filesystems have a top-level directory structure that looks something like this:

The Windows filesystem is similar, but with one major difference: on Windows, different storage devices have their

own “tree” (e.g., C:\, D:\, and so on). On Unix-like systems, there is a single “tree”, and each storage device

is mounted (attached) to the tree at a different location.

where am i?#

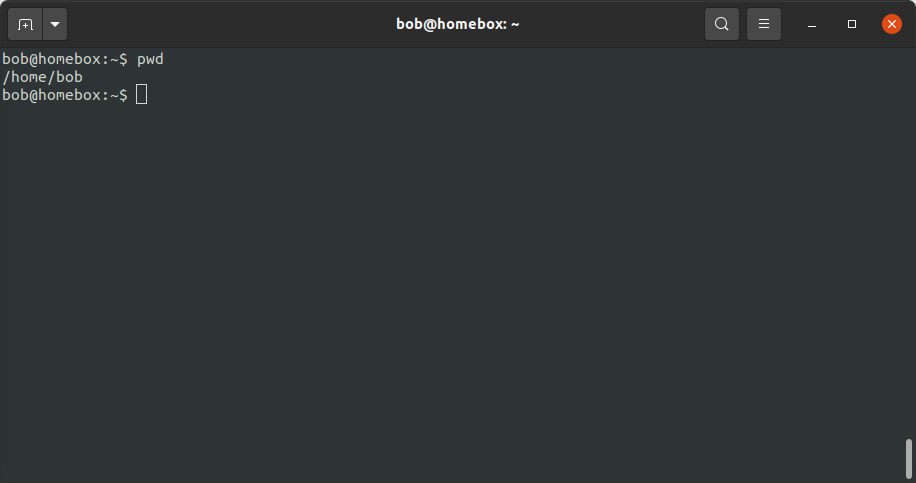

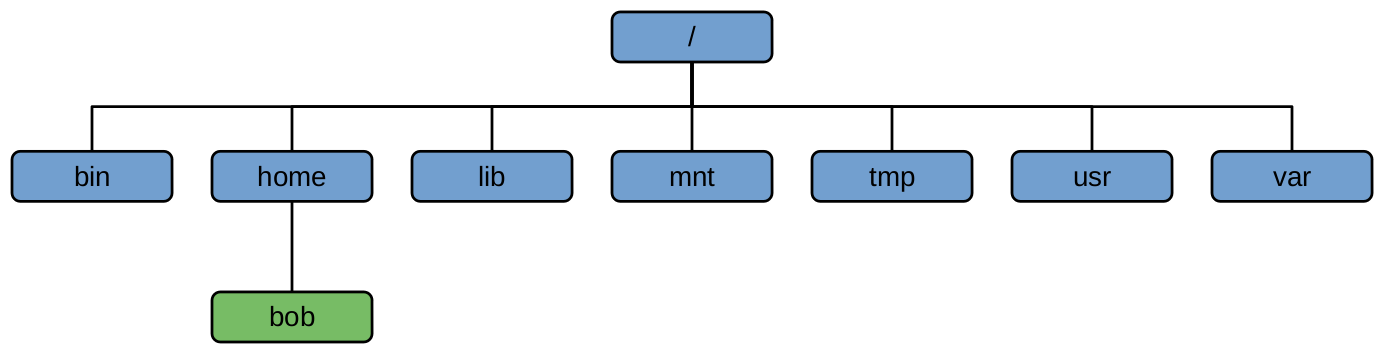

When we are working in the shell, we are always in a single directory: the current working directory. To find out

what that directory is, we can use the pwd (“print working directory”) command:

pwd

In our filesystem tree diagram, we are here:

Most of the time, when you first log in or open a terminal, you will be in your home directory. On Linux

systems, this directory is usually located here:

/home/<your username>

Every user account is given a home directory - very often, this is the only directory where “regular” (non-administrator) users are allowed to write files.

Note

In OSX, your home directory is usually located at /Users/<your username>. In Windows 10 and 11, it is located at

C:\Users\<your username>.

navigating the filesystem#

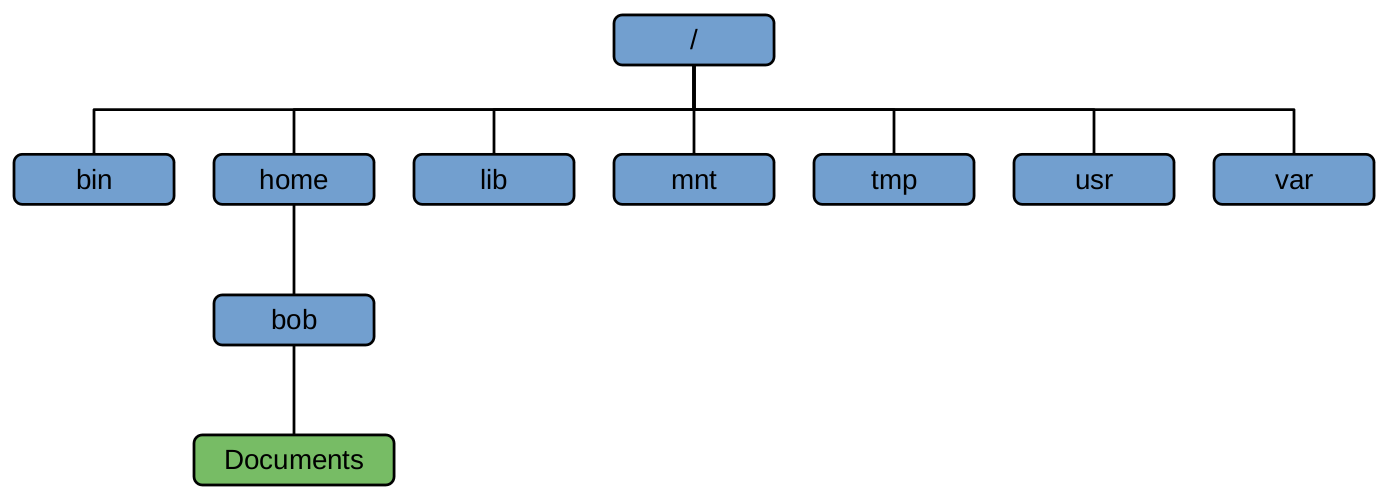

To change the working directory in the shell, we use the cd (“change directory”) command, along with the

pathname of the directory we want to move to. For example, to change from our home directory to Documents, we

would type:

cd Documents

In our tree diagram, we are now here:

By itself (i.e., without including a pathname), cd will return us to our home directory. If you type

the following:

cd

you should see that you are returned to your home directory (feel free to check this using pwd).

pathnames#

When working with pathnames, there are two ways that we can specify them: as absolute pathnames, or as relative pathnames.

absolute pathnames#

Absolute pathnames start with the root directory (remember, on Unix-like filesystems, this is /) and follow

the tree through every branch until it reaches the specified file or directory. For example, the absolute path to

my Documents folder is:

/home/bob/Documents

That is, we start at the root directory (/), then move to the home directory, then the directory corresponding

to my username (bob), then the Documents directory.

Using an absolute pathname, then, we can navigate from the Documents directory back to our home directory by

specifying the absolute pathname to our home directory:

cd /home/bob

relative pathnames#

Relative pathnames, on the other hand, start in the current working directory. This brings us to two important notations that are used to represent relative positions in the file tree: . and ...

In a relative pathname, . refers to the directory itself, and .. refers to the parent directory (the directory immediately above it in the hierarchy).

So, if we are in the Documents folder and we want to go back to our home folder using a relative pathname, we can

do so by specifying the pathname to our home directory, relative to the Documents directory:

cd ..

As before, you should see that this has returned you to your home directory, which you can check using pwd.

creating a new directory#

Now that we know a bit more about how to navigate the filesystem from the command line, we can create a new directory,

using the mkdir command.

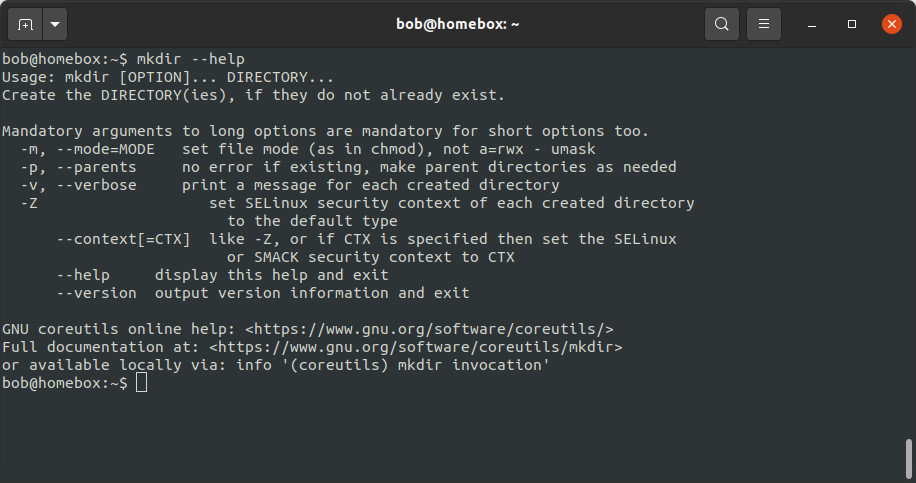

Before you jump straight in, though, we’ll use the --help option to show information about how to use the command:

mkdir --help

Here, as before, we see that we have (optional) options - remember that the square brackets indicate that these

are not required for the program to run. We also have a required input, DIRECTORY, indicated by the lack of square

brackets. This makes sense, as we can’t exactly tell the computer to create a new directory without also telling it

what to call the directory.

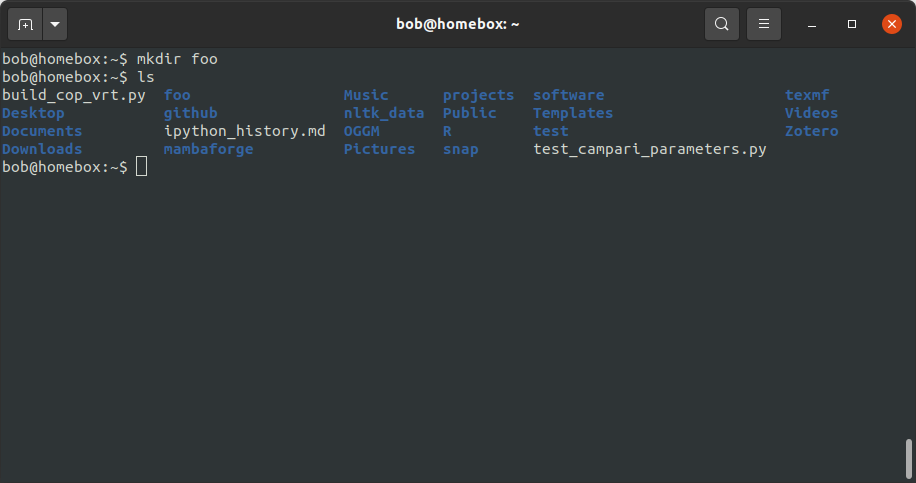

So, let’s use mkdir to create a new directory called “foo”:

mkdir foo

Now, use ls to list the contents of the current directory - you should see your new directory, foo, listed along

with the previous contents:

file and path names#

Before we move on to using the shell to work with files, we’ll focus on a few different rules for file and directory names.

To start with, filenames (like commands) are case sensitive - this means that

Fooandfooare two different files/directories.Filenames that begin with a period (

.) are hidden - we will look at this more a bit later, but in practice this means that by default,lswill not actually list these files.File extensions are typically not super-important on Unix-like systems: you can name files any way that you like, because the operating system has other ways of identifying the file type. That said, some applications may still use file extensions to identify/work with files, so it’s usually still a good idea to use them in practice.

File and directory names cannot include

/- as we have seen, this character is used for delimiting directories in the filesystem, which means it can’t show up in the middle of a filename.As a general rule, it’s a good idea to only use alphanumeric characters (letters and numbers), periods (

.), dashes (-), and underscores (_) in file and directory names.

By far the most important rule for file and directory names in Unix-like systems, though, is this one1:

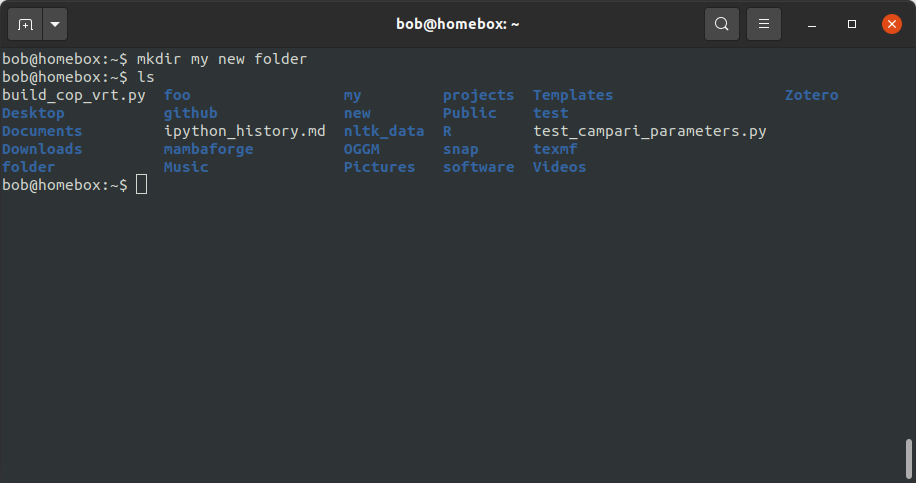

Remember: spaces are used as delimiters between parts of a command. For example, try the following command:

mkdir my new folder

You might think that this will create a new directory, “my new folder”, in the current working directory, right?

Not quite - we can see what actually happens using ls:

As you can see, this command has created three new directories: my, new, and folder. Because

mkdir allows for multiple inputs, it sees each “word” in the directory name as a separate directory.

In the long run, it is safer and much less unpredictable to use underscores or dashes to represent spaces.

notes#

- 1

Strictly speaking, it is possible to use spaces in file and directory names. That said, it makes things far more difficult to manage, because you always have to be on the lookout for rogue spaces entering your commands unnoticed. As with capes, it is better to be safe than sorry.