input/output#

In this exercise, we’re going to use a collection of historic meteorological observations, downloaded from the UK Met Office.

Our goal is to figure out which station has the most observations, using a combination of different shell programs and techniques.

To follow along, make sure to first download the data file.

sample data#

Once you have downloaded the file, use the shell to navigate to the directory containing the file, then use the following command to extract the contents of the file:

tar xvzf sample_data.tar.gz

This uses the tar (from “tape archive”) command to unzip (the z option) and extract (x) the files

contained in the archive. The v option (“verbose”) means that as each file is extracted, its name is printed to the

screen, while the f option tells tar to read from the filename given.

You should see that this creates a new directory, sample_data, which contains the files we’ll use for the rest of

this exercise - use cd to move to this directory.

We’ll start by looking at wc (“word count”), which counts the number of lines, words, and characters in a file.

Navigate to where you have saved the sample_data folder, then use ls to show the contents of the directory.

You should have 37 .txt files, corresponding to 37 different Historic Met Station datasets.

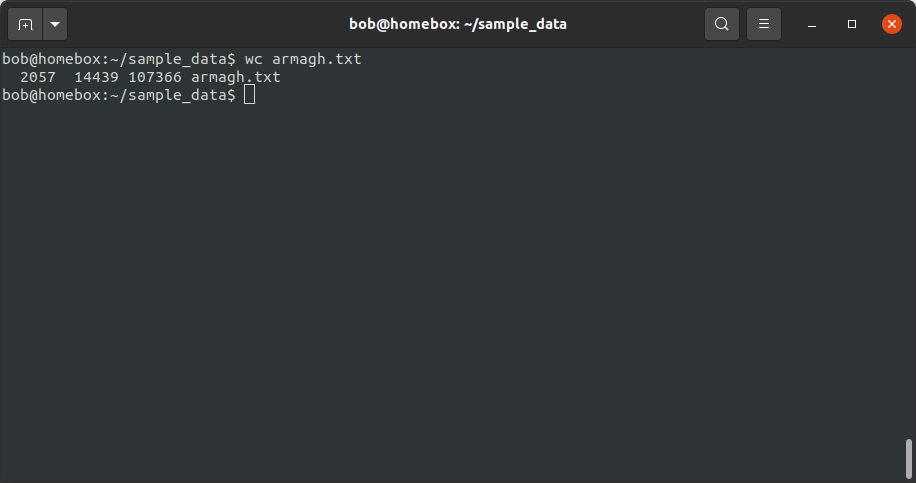

Let’s start by looking at the wc output for a single file, armagh.txt:

wc armagh.txt

From this, we see that armagh.txt has 2057 lines, 14439 “words”, and 107366 characters. If we are only

interested in the number of lines in the file (assuming that 1 line = 1 observation), we can use the -l option:

wc -l armagh.txt

pipes and filters#

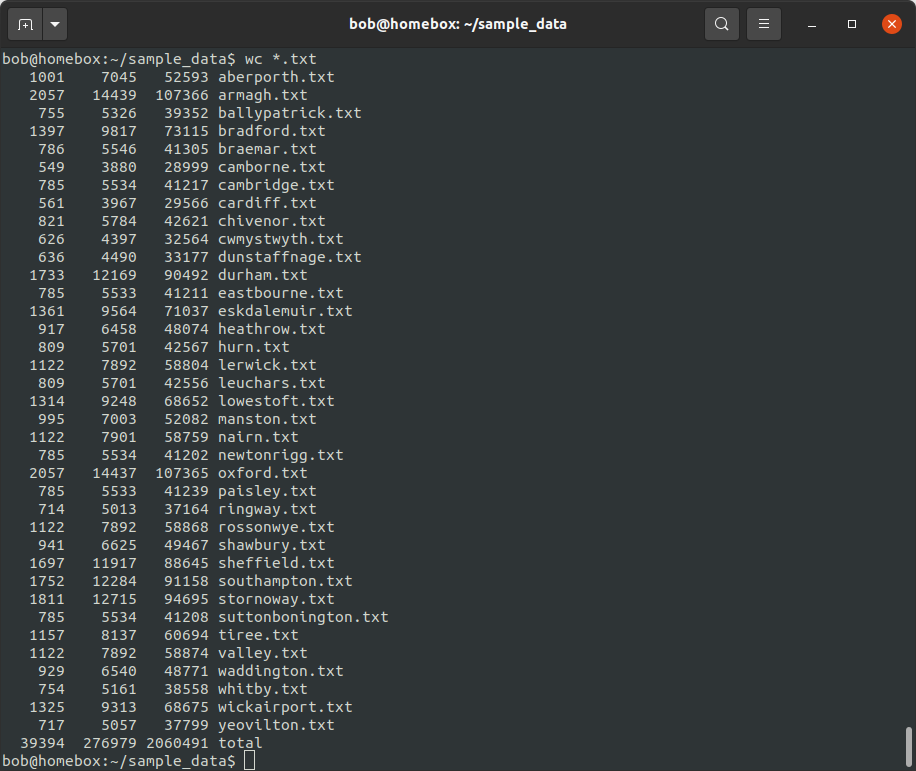

We can also use a wildcard expression to pass all of the filenames matching a given pattern to wc:

wc *.txt

With multiple files, wc prints information for each file (in alphabetical order), along with the total for all

of the files.

This means that we’re part of the way to our answer: we now have an idea of how many lines are in each file. Next, we need some way of figuring out which of these values is the largest.

One way that we can do this is by using a filter (a command that takes some input, does some operation, and outputs the results). Some commonly used filters include:

command |

function |

|---|---|

|

sorts a file/input |

|

removes duplicated lines from a sorted file/input |

|

outputs lines that match a specified pattern (more on this later) |

|

formats input text |

|

outputs the first few lines of a file/input |

|

outputs the last few lines of a file/input |

|

translates characters (e.g., upper to lowercase and vice-versa) |

|

‘stream editor’, for more sophisticated text translation |

|

a programming language designed for constructing complex text filters |

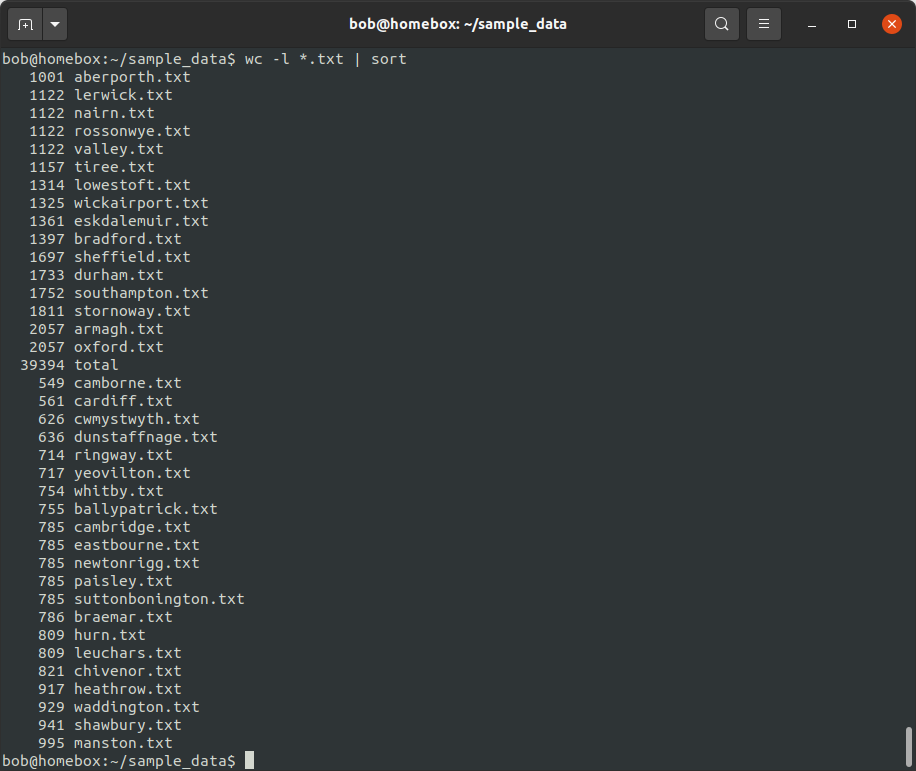

To sort the output of the wc command, then, we can use the sort command.

To do this, we need to pass the output of wc to sort, using a pipe (|). This tells the shell that we

want to use the output of the command on the left as input to the command on the right:

wc -l *.txt | sort

By default, sort sorts a line in ascending order, alphabetically. This means that 1001 comes before

549 (because 1 comes before 5), even though 549 < 1001.

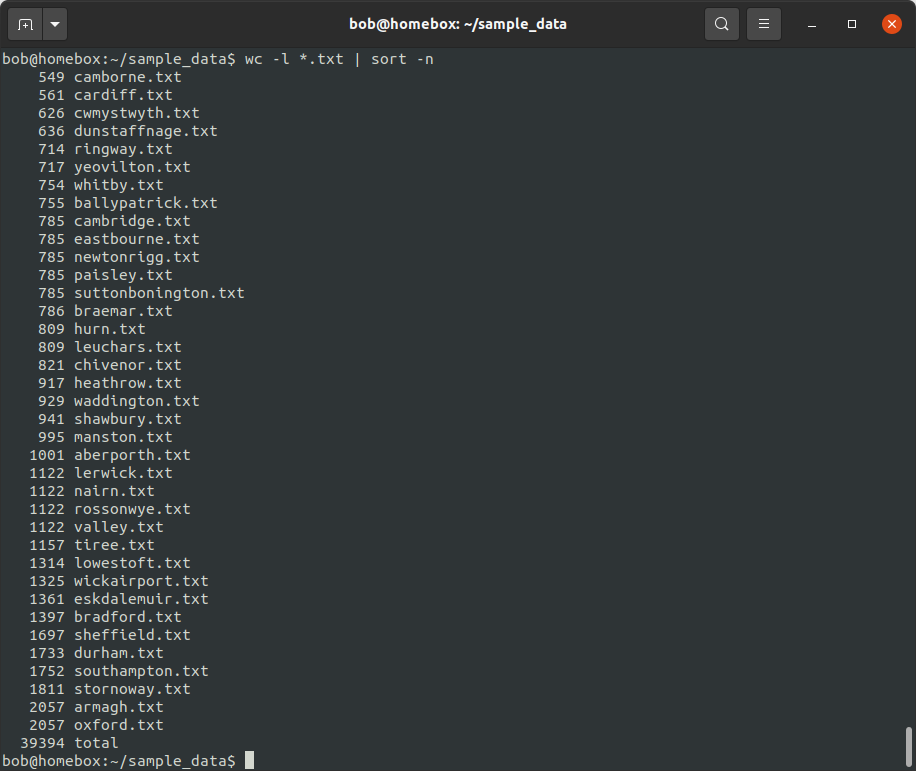

To force sort to sort values numerically (such that 549 comes before 1001), we need to use the -n option:

wc -l *.txt | sort -n

This gives us the number of lines in each file, sorted in ascending order - we can see that Camborne has the

fewest lines (549), while Armagh and Oxford have the most lines (2057). We can also use the -r option to sort

in descending order:

wc -l *.txt | sort -rn

We don’t have to stop here - we can use more than one | to continue passing the output of one command to another.

For example, we can pass the output of sort to head, to view the top 5 stations:

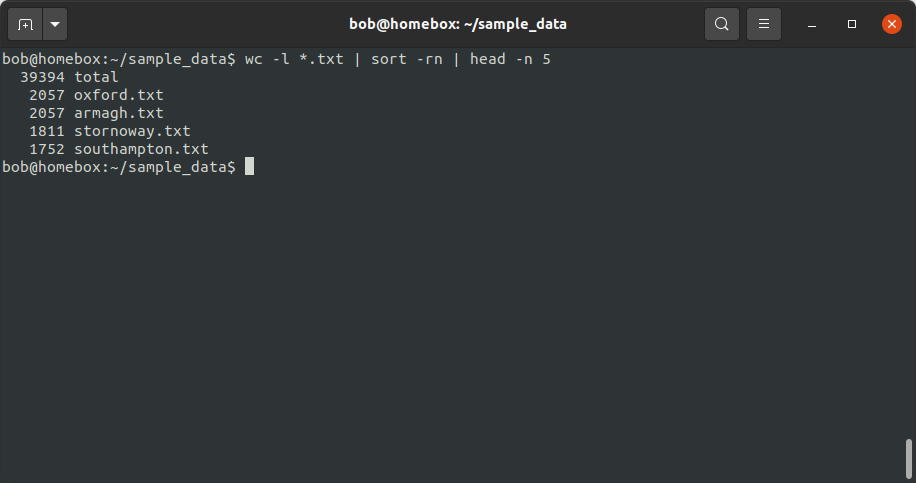

wc -l *.txt | sort -rn | head -n 5

Now, you’ll notice that we need some way of removing the total from the output.

Question

Can you think of a way to do this, using the techniques introduced above?

grep and regular expressions#

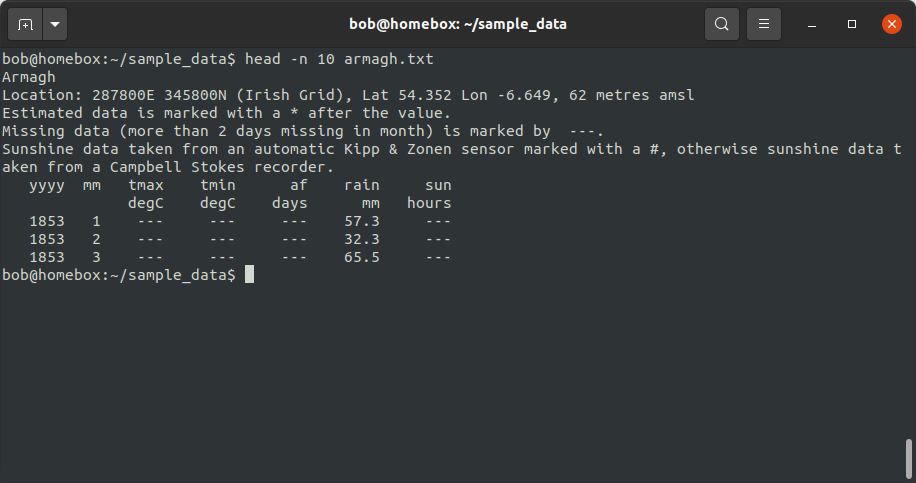

First, let’s take a closer look at our files. To see the first few lines of a file, we can use the head command:

head -n 10 armagh.txt

This output shows us that not every line of the file corresponds to an observation - in fact, in this example, the

observations don’t actually start until the 8th line of the file. We could simply use the number of lines in each file

and subtract the number of header lines, but we don’t necessarily know that each file has the same number of header

lines.1

So, we’ll need to find another way to get the information we’re looking for.

Look again at the output of head on armagh.txt, and pay attention to the first line that shows us an

observation:

1853 1 --- --- --- 57.3 ---

This line begins with three spaces, followed by four digits (representing the year). In fact, all lines with observations follow this pattern.2

To search for patterns in text files, we can use grep. This incredibly powerful program uses

regular expressions to find text matching a pattern. For example,

the pattern of “a line that begins with three spaces followed by four digits” can be represented as the following,

which makes use of some of the wildcards we introduced previously:

^\s{3}[[:digit:]]{4}

Starting from the left:

^means to match the empty string at the beginning of a line - this way, we won’t accidentally find four digits in the middle of a line\smeans to match a space character{n}means “match exactly n of the previous item” - so\s{3}means “match exactly three spaces”[[:digit:]]{4}means “match exactly 4 numeric characters”

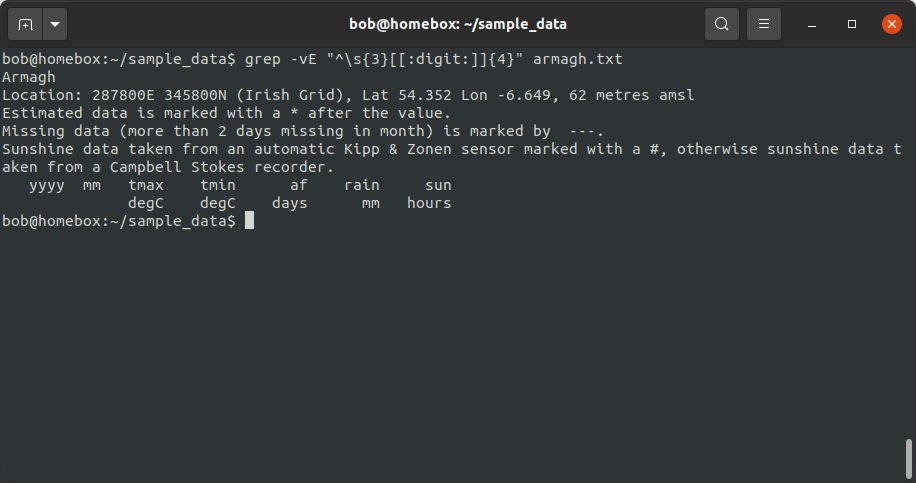

We can then call grep using the -E option (for extended regular expressions), to show all lines in the file

that contain at least one match for our pattern:

grep -E "^\s{3}[[:digit:]]{4}" armagh.txt

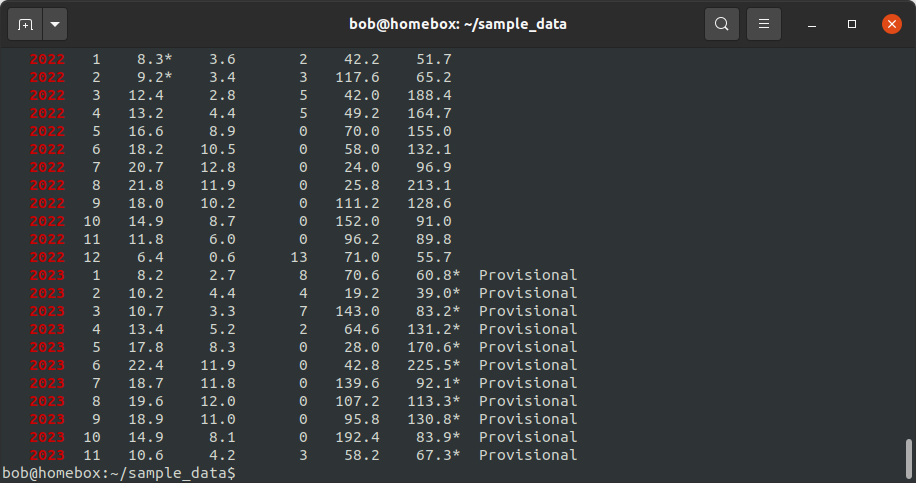

Note that your output may look different - for example, it may not highlight the matching text on each line.

We can also use the -v option to “invert” the matching - now, grep will only print those lines that do not

match the pattern:

grep -vE "^\s{3}[[:digit:]]{4}" armagh.txt

Later, we will make use of both of these commands to help us split the original .txt files into two separate

files.

Using grep only shows us how many lines match (or don’t match) the pattern, but we want to easily count the number

of lines that match the pattern, so we need at least one more step to reach this part of our goal.

redirecting output#

Now that we have seen how we can use the pipe operator (|) to pass the output of a command to another command,

let’s see how we can redirect the output of a command from the screen to a file, using >. Similar to |,

> tells the shell to take the output of the command on the left and write it to the file on the right.

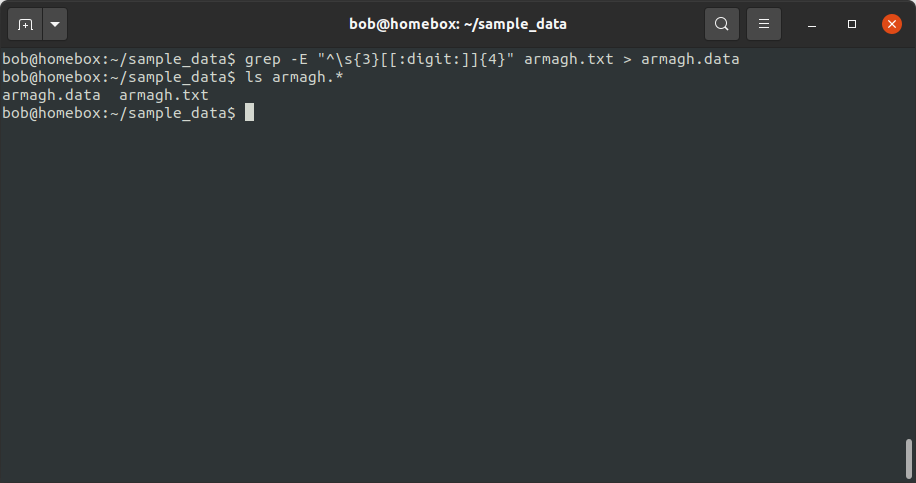

For example, if we wanted to split our data files into two parts, a header and the observations, we could start by

redirecting the output of grep to a new file, armagh.data:

grep -E "^\s{3}[[:digit:]]{4}" armagh.txt > armagh.data

You should notice two things here: first, the output of grep is no longer printed to the screen, because it

has instead been “printed” to the file armagh.data; second, using ls, you should see that there is a new file

in this directory.

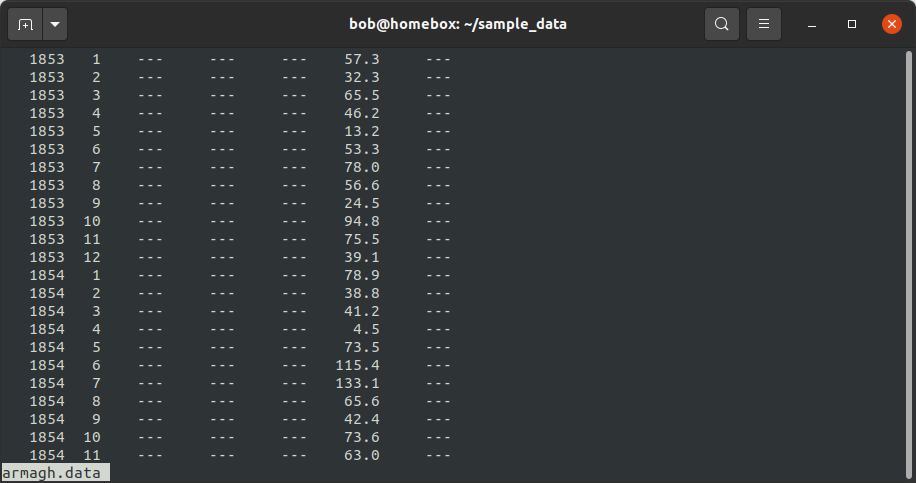

To check that the correct lines have been printed, use the less command to see the contents of the file:

less armagh.data

Once you are happy that the observations have been printed to the file correctly, press q to close less.

In the same way, we can also use grep with the -v option to split the header lines into a separate file:

grep -vE "^\s{3}[[:digit:]]{4}" armagh.txt > armagh.head

As before, you can use ls to check that this new file has been created, and use less to view the contents of

the file.

Tip

When using command > file, file is overwritten with whatever the output of command is.

If we want to append the output of command to an existing file, we use >>:

command >> file

If file does not already exist, it will be created.

reading input#

In addition to redirecting the output of a command to a file, we can also redirect input from a file to a command

using <:

command < file

For example, if we wanted to get a sorted list of all of the txt files in a directory3, we could first redirect the

output of ls to a file:

ls *.txt > file_list.txt

Then use < and sort to see a sorted list of the files:

sort < file_list.txt

We can also redirect this output to a new file, using >:

sort < file_list.txt > sorted_files.txt

Note

The order doesn’t matter here - we could also write:

sort > sorted_files.txt < file_list.txt

and we would get the same result - the important thing is that the > and < operators come after all of the

other options and arguments to the command (in the case, sort).

next steps#

We’re still only part of the way to our goal, however - we have seen how we can split the original files into .data

and .head files using grep and >, and how we can use wc, |, and sort to figure out which files

have the most lines.

There’s another piece missing: we need to split multiple files. In the next lesson, we’ll look at how to do this, and how we can combine all of these different commands into a single program (a “script”) so that we can repeat this process whenever we update or add to our data.